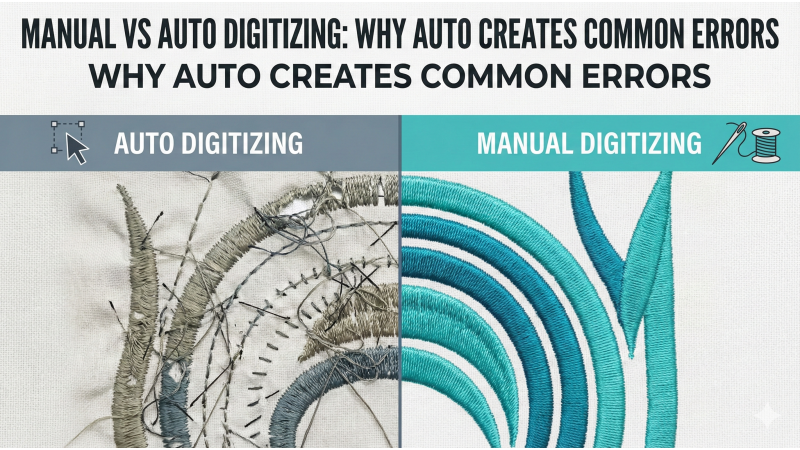

Manual vs Auto Digitizing: Why Auto Creates Common Errors

Digitizing is the invisible architecture beneath every embroidered design — the quiet set of decisions that determine whether your machine glides smoothly or tangles itself into a thread labyrinth. With the rise of modern software, many embroiderers are tempted by the promise of auto digitizing tools that instantly transform an image into stitches. Yet the gap between a fast result and a professional result is wide. Manual digitizing, with all its deliberate choices, still shapes cleaner, smoother, and more durable embroidery.

Auto digitizing remains an attractive shortcut, especially for beginners, but those who have observed how thread behaves on fabric — the stretch, the push, the tension — know that precise human judgment outperforms automated algorithms. Many embroiderers study videos like this breakdown of manual vs auto decision-making to understand why the machine often needs a human steward instead of a software guess.

What Is Auto Digitizing?

Auto digitizing converts a flat graphic into stitches with minimal input. The software analyzes color regions and edge boundaries, then assigns stitch types based on prebuilt rules. It sounds intuitive, but embroidery requires more than pattern recognition. Machines don’t sew pixels — they sew tension, fabric behavior, density, and pull in motion. This is why even experienced digitizers caution newcomers after watching examples such as auto-digitizing mistake demonstrations.

What Is Manual Digitizing?

Manual digitizing is deliberate. It involves choosing stitch directions, defining pathing, adjusting compensation, and selecting underlay with intention. Every point placed on-screen reflects how the machine will behave physically. It’s craftsmanship, not automation — and it’s why professional digitizers consistently prefer hands-on control for commercial logos, small lettering, and tight details.

Why Auto Digitizing Creates Common Errors

Auto digitizing relies entirely on software logic instead of embroidery logic. It evaluates artwork visually, not structurally. It has no sense of how polyester thread shrinks on a stretchy fabric, how density affects puckering, or how pull compensation protects borders from collapsing. This disconnect is why so many embroiderers study resources like this explanation of auto-digitizing limitations.

1. Poor Pathing and Too Many Jumps

Auto digitizing does not understand efficient needle travel. It often assigns random sequences, creating long jumps, excessive trims, and awkward travel stitches. This leads to slower production and outlines that drift out of position. Videos such as machine pathing critique guides show how auto tools stumble where manual pathing glides.

2. Incorrect or Excessive Density

Auto algorithms often apply a single density setting across an entire design. This creates over-stitched areas that pucker or under-stitched areas that look patchy. Manual digitizers adjust density based on fabric stretch, stabilizer type, and element size.

3. Poor Underlay Choices

Underlay provides the foundation for clean embroidery. When auto digitizing misjudges underlay — too much or too little — the design either becomes bulky or collapses. Manual digitizing chooses underlay based on real-world needs, not presets.

4. Distorted Shapes and Inaccurate Details

Auto digitizing struggles to handle curves, thin shapes, tiny highlights, and fine outlines. It often fills areas with stitch types that won’t stitch cleanly. This is one of the issues commonly highlighted in articles like this guide on mistakes that ruin embroidery.

5. No Pull or Push Compensation

Every fabric behaves differently. Without compensation, satin borders shrink inward, fills leave gaps, and outlines drift. Auto tools rarely apply proper pull/push adjustments, resulting in distorted shapes and misaligned details.

6. Incorrect Stitch Types for Different Areas

Auto digitizing might place satin stitches on areas far too wide or assign long fills on tiny elements. These mismatches cause looping, thread breaks, or uneven texture. Manual digitizers choose stitch types based on size, shape, and purpose — that human judgment is irreplaceable.

7. Inconsistent Stitch Angles

Stitch angles influence shading, smoothness, and fabric tension. Auto tools randomly generate angles without considering flow or stability. A trained digitizer uses angles to guide the viewer’s eye and control distortion.

8. Poor Lettering Results

Lettering exposes every weakness in auto digitizing: missing counters, uneven spacing, poor pull compensation, or overly dense columns. Clean lettering requires knowledge, not presets. For deeper understanding, resources like this lettering and detail-focused guide provide helpful insight.

When Auto Digitizing Can Be Useful

Auto digitizing isn’t always a villain. For simple shapes, quick mockups, or designs where precision is not critical, it can generate a workable base. Some digitizers auto-generate a draft, then refine it manually. This hybrid approach saves time while maintaining quality.

When Manual Digitizing Is Essential

Manual digitizing is indispensable for logos, intricate artwork, complex gradients, and anything requiring commercial-grade reliability. When detail matters — curves, textures, stitching order, underlay logic, compensation — software shortcuts simply cannot match experience.

Why Manual Digitizing Produces Better Results

Manual digitizers make decisions software cannot. They evaluate fabric type, test stitch-outs, adjust density based on tension, refine pathing to eliminate unnecessary jumps, and ensure that every angle supports the design’s structural integrity. It’s a blend of engineering and artistry.

Those who study professional workflows understand why precision matters, especially after exploring tutorials like this practical digitizing walkthrough and similar resources across the embroidery community.

Conclusion

Auto digitizing is fast, convenient, and occasionally helpful — but it is not a substitute for skill. The more complex the artwork, the more essential manual digitizing becomes. When stitch quality, clarity, registration, and durability matter, human judgment outperforms automation. Every embroiderer who grows from beginner to expert eventually sees the same truth: great embroidery starts long before the machine runs. It begins with thoughtful digitizing, steady hands, and choices made with a deep understanding of how fabric and thread behave under motion.

Leave a comment